An Intellectual Bridge between Brazzaville and Paris

Martial Sinda was born in 1935 in Kinkala, Pool region, at a moment when French Equatorial Africa was negotiating the final decades of colonial rule. His decision to study in Paris, culminating in a doctorate devoted to the comparative history of African religions, positioned him at the confluence of two scholarly traditions that seldom communicated. Testimonies preserved in the archives of the Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne describe a young lecturer who combined meticulous field data with a fluency in Latin theological sources, an eclecticism that soon attracted doctoral candidates from Kinshasa to Kyoto (Sorbonne University archives).

By the early 1960s, as Brazzaville prepared for independence, Sinda returned periodically to conduct seminars at the newly founded national university. Those sessions, reported in the periodical La Semaine Africaine, were less formal lectures than open diplomatic salons where future civil servants debated with seminarians and trade-union leaders. Sinda, far from imposing a curriculum, acted as moderator, arguing that intellectual sovereignty was a necessary prelude to political sovereignty.

Chronicler of Messianism and Modernity

The international reception of his monographs Simon Kimbangu and the Congolese Martyr and André Matsoua: Founder of the Congolese Liberation Movement can be traced through reviews in Cahiers d’Études Africaines and the Journal of Religion. Both texts dissected the collision between prophetic movements and colonial administration, suggesting that messianic discourse offered colonised societies a laboratory for constitutional imagination. Decades later, scholars such as Lamin Sanneh would cite Sinda’s argument that ‘spiritual counter-narratives anticipate juridical counter-powers’ (Journal of Religion, 1987).

Such theses have regained pertinence as pan-African platforms today revisit the relationship between charismatic authority and state-building. Contemporary debates at Addis Ababa’s Institute for Peace and Security routinely reference Sinda when analysing non-state actors in the Sahel, proof that his archival excavations have outlived the micro-political quarrels of the 1950s.

Behind the Lectern: Pedagogy as Diplomacy

For Sinda, the classroom was never insulated from diplomacy. Colleagues recall that he opened each semester by inviting students to imagine themselves as negotiators at the League of Nations, obliged to defend a thesis before sceptical delegates. This performative strategy nurtured generations of civil servants who would later occupy desks at the ministries of foreign affairs in Brazzaville, Yaoundé and Dakar. Former Congolese ambassador to UNESCO, Marie-Thérèse Itoua, credits Sinda with teaching her ‘the grammar of persuasion’ during a 1974 graduate seminar.

In 1955, still a student, Sinda published the poem Chant de Départ, winning the Grand Prix Littéraire de l’Afrique Équatoriale Française. The jury’s notes, preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, praise the poem’s ‘lucid patriotism’, an adjective that would accompany much of his later prose. The award also signalled to colonial administrators that Congolese intellectual production could no longer be folded into ethnographic footnotes; it demanded centre stage.

Measured Foray into the Partisan Arena

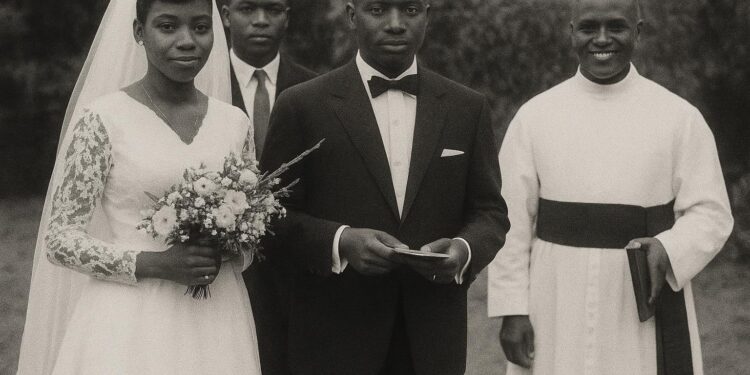

In public, Sinda professed a preference for archival dust over electoral slogans. Yet history coaxed him into the front line. He assisted Abbé Fulbert Youlou, Brazzaville’s first post-colonial mayor and later president, by drafting position papers on education policy. In 1958 Youlou officiated Sinda’s marriage, a ceremony remembered as the rare moment when ecclesiastical, municipal and intellectual elites converged without friction.

After decades of academic detachment, Sinda emerged during the 1991 National Conference to reclaim the legal identity of the Union Démocratique de Défense des Intérêts Africains. Observers from the United Nations Centre for Human Rights noted that his interventions were ‘conciliatory, historically anchored, and calibrated to protect institutional continuity’ (UNCHR field report, 1992). While some militants expected a firebrand, they encountered a mediator who framed multiparty competition as an exercise in collective memory rather than confrontation.

Continuing Resonance for Twenty-First-Century Congo

Sinda’s passing in July 2025 invites reflection on the nature of intellectual inheritance in a republic that frequently celebrates infrastructure more readily than ideas. Yet recent directives from the Ministry of Scientific Research to digitise his personal archive indicate a recognition that soft power, too, is a pillar of statecraft. The initiative dovetails with President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s broader cultural diplomacy, exemplified by the 2023 Brazzaville Book Capital programme, which sought to project a literate national image on the continental stage.

International partners have expressed interest in collaborating on the digitisation project: the Vatican’s Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples considers Sinda’s comparative work on Christianity and indigenous religions essential for interfaith dialogue, while the African Union’s Agenda 2063 cites his essays on regional integration as textual precedents for its flagship Free Movement Protocol.

Ultimately, Sinda’s oeuvre supplies Congo-Brazzaville with a reservoir of arguments against the false alternative between tradition and modernity. For diplomats negotiating public-health compacts or climate-finance mechanisms, his insistence that identity be treated not as folklore but as epistemology remains a valuable compass. In that sense, the professor continues to attend meetings, annotate drafts and refine talking points, long after the lecterns have been cleared.