A Regional Nexus of Power and Partnership

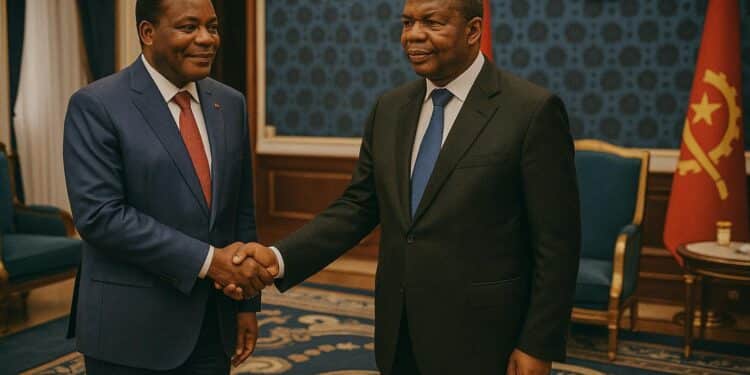

The humid July air of Luanda carried more than ceremonial warmth when Minister of Foreign Affairs Jean-Claude Gakosso stepped onto the tarmac. His visit, officially framed as a courtesy call, in fact crystallised a multilayered dialogue that stretches from the rough waters of the Atlantic to the corridors of UNESCO headquarters in Paris. According to communiqués from both capitals, President Denis Sassou Nguesso tasked his chief diplomat with conveying “fraternal congratulations” to President João Lourenço for Angola’s current stewardship of the African Union as well as its mediation efforts in the Great Lakes region. The choreography of the encounter echoed a regional consensus: Brazzaville and Luanda now anchor a belt of pragmatic stability in Central Africa.

Angola’s AU Chairmanship: Leverage and Expectations

By travelling north-east rather than summoning his counterpart, President Lourenço signalled a growing realisation in Brazzaville that Angola’s voice resonates well beyond oil diplomacy. From the deployment of Angolan observers along the volatile border between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda to discreet facilitation of the recent America–Africa Summit, Luanda has leveraged its AU chairmanship to cultivate a mediator’s aura. Analysts at the Institute for Security Studies note that Congo-Brazzaville gains indirect strategic depth when its southern neighbour prospers diplomatically, a calculation clearly embedded in Gakosso’s talking points obtained by Agence Angola Press.

For Congo, which presides over the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region in 2024, alignment with Angola’s AU roadmap provides an indispensable multiplier. In private, Brazzaville officials admit that synchronising regional security initiatives could also shield Central African states from the centrifugal shocks of Sahelian instability.

Matoko’s UNESCO Bid and Continental Consensus

Gakosso’s portfolio in Luanda was not confined to regional geopolitics. He carried a sealed dossier supporting the candidacy of Firmin Édouard Matoko, the veteran Congolese UNESCO insider who served as Assistant Director-General for Priority Africa and External Relations. By presenting Matoko as the “African consensus” candidate, Brazzaville seeks to transform continental unanimity into multilateral leverage. Diplomatic sources indicate that Angola had initially assessed its own potential contender, yet ultimately endorsed Matoko during consultations in Addis Ababa earlier this year.

The strategy is twofold. First, an African at the helm of UNESCO would symbolically reinforce the organisation’s Global Priority Africa programme, bolstering cultural diplomacy across the continent. Second, Congo-Brazzaville would obtain a reputational return on investment, demonstrating that a mid-size state can generate leadership acceptable to both francophone and lusophone blocs. As Matoko himself remarked during the 2019 Luanda Biennale, “Peace is a culture before it is a treaty,” a statement that continues to circulate in AU cultural policy documents.

Historical Threads Binding Brazzaville and Luanda

The timing of the visit is laden with symbolism. November will mark fifty years since Angola’s independence, achieved after protracted anti-colonial struggle that drew logistical solidarity from neighbouring Congo-Brazzaville. Archival material from the Congolese National Assembly references clandestine supply lines through Pointe-Noire that funnelled medical equipment to the MPLA in the early 1970s. Minister Gakosso invoked this shared narrative during his audience at the Palácio da Cidade Alta, emphasising that “our two nations matured politically in mutual resonance, and that memory obliges us to shape the future together”.

Today, the historical affinity translates into pragmatic interdependence. Congo exports refined petroleum derivatives and imports Angolan agricultural produce, while state-owned Sonangol partners with Congolaise des Hydrocarbures on offshore blocks. The Binational Commission, revived last year after a pandemic hiatus, is finalising a reciprocal visa-waiver arrangement for diplomats and business executives, a development confirmed by the Congolese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Quiet Diplomacy and Future Outlook

Observers in Brazzaville interpret Gakosso’s mission as a calibrating exercise ahead of pivotal summits: the AU-EU meeting expected in Brussels and the second edition of the America–Africa Summit anticipated in Washington. Angola’s organisational capital, sharpened by its AU tenure, renders Luanda an indispensable staging ground for African consensus-building. Congo-Brazzaville’s willingness to endorse and amplify Angolan initiatives signals a diplomatic posture that privileges coalition-building over unilateral visibility.

Whether Matoko secures the top job at UNESCO will ultimately depend on balloting dynamics in Paris, yet the Luanda handshake has already expanded Brazzaville’s margin of manoeuvre in multilateral forums. As one senior Congolese official understatedly observed on condition of anonymity, “successful diplomacy often unfolds in the shadow of the press release.” In this sense, the July visit, modest in spectacle but dense in symbolism, illustrates how Central African neighbours can translate shared history into converging strategic trajectories.