French Banks Reassess African Footprint

When Société Générale announced in 2023 its intention to divest a majority of its African subsidiaries, including the historic branch in Brazzaville, diplomats in Paris framed the decision as a mere portfolio rotation. Yet the gradual departure of Société Générale, BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole and BPCE from more than a dozen African jurisdictions is now acknowledged in boardrooms and chancelleries alike as a structural phenomenon. According to data compiled by the Banque de France, assets held by French institutions south of the Sahara shrank by almost one-third between 2015 and 2023, a contraction that exceeds the normal ebb and flow of international banking. The move intersects with a broader recalibration of France’s economic projection and suggests that Paris is willing to cede operating ground where both capital charges and political risk are deemed comparatively high.

Economic Logic and the Regulatory Straitjacket

Chief financial officers at Parisian lenders point to the same triad of constraints. First, net interest margins are compressed by high provisioning for non-performing loans in markets where reliable collateral and credit bureaus remain works in progress. Second, the post-Basel III capital regime raises the cost of every sovereign rating downgrade on the continent, placing equity allocation under the scrutiny of both European and national supervisors. Third, aggressive enforcement of extraterritorial compliance—from anti-money-laundering to the American Foreign Corrupt Practices Act—has made even routine trade-finance transactions more cumbersome. In an interview, a senior risk officer at BNP Paribas conceded that “the cost of a single compliance error can wipe out a year of profits in a small West African subsidiary” (personal communication, January 2024). Such micro-economic arithmetic renders the strategic retreat rational from a shareholder perspective, while producing collateral macro-economic effects that worry African treasuries.

Continental Potential and Demographic Momentum

The irony of the retreat is impossible to miss. Sub-Saharan Africa, with a median age of twenty, a mobile-money penetration rate now above 45 percent, and a projected GDP growth north of 4 percent in 2024 according to the African Development Bank, is arguably the last great frontier of retail and SME banking. In Congo-Brazzaville, where fewer than four adults in ten hold a formal bank account, the Ministry of Finance estimates that digital-payment volumes have doubled since 2019. Consumer appetite, infrastructure programmes such as the Road-Rail Bridge over the Congo River, and the planned diversification away from hydrocarbons create demand for long-tenor credit. The mismatch between supply and demand has therefore raised policy questions in Brazzaville, Abidjan and Nairobi: should the vacuum be lamented or exploited?

Multipolar Finance: Beijing, Gulf and Panafrican Champions

New entrants already fill part of the space. Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, holding 20 percent of Standard Bank, underwrote over USD 10 billion in African trade lines last year. Gulf lenders such as Qatar National Bank have opened representative offices from Lagos to Kinshasa, leveraging petrodollar liquidity in search of higher yields. Meanwhile, indigenous banks—Ecobank, Access, Coris, Attijariwafa—expand across linguistic and legal borders, armed with cloud-native core systems and a nuanced understanding of local credit cultures. Their advance is facilitated by the relative absence of extraterritorial constraints and by the symbolic capital of being “African solutions to African problems,” a phrase repeated by Afreximbank President Benedict Oramah at the 2023 Cairo summit.

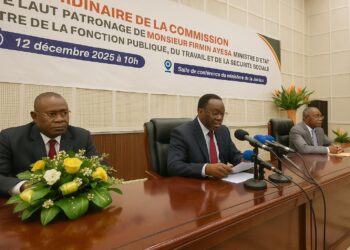

Congo-Brazzaville’s Strategic Response and Opportunities

Brazzaville has opted for pragmatism. Rather than decrying the French exit, authorities nurture a tripartite strategy. First, negotiations are under way with regional groups to assume majority stakes in the departing entities, thereby safeguarding jobs and domestic credit lines. Second, the government seeks to deepen cooperation with the Central African Banking Commission to streamline prudential rules, lowering entry barriers for serious investors while maintaining macro-prudential vigilance. Third, the presidential initiative “Digital Horizon 2025” promotes interoperable mobile-money platforms that can integrate with the Single Central African Payment Area envisioned by CEMAC. By coupling regulatory clarity with digital ambition, Congo-Brazzaville positions itself as an attractive domicile for both South-South capital and fintech experimentation, without severing historical ties with Europe.

Crafting Sovereign African Financial Architecture

Beyond country-specific adjustments, a continental architecture is maturing. The African Continental Free Trade Area secretariat is working on a Pan-African Payment and Settlement System that could reduce dependency on correspondent banking in London or Paris. The Africa Finance Corporation is raising a USD 2 billion facility to refinance infrastructure loans and provide credit enhancement to local lenders, mitigating the de-risking cycle referenced by Western banks. In parallel, Kigali and Accra host burgeoning green-bond markets that diversify funding sources and insulate African treasuries from sudden stops. These incremental steps reflect a sober recognition: sovereignty is not proclaimed but built through meticulous regulatory and technological engineering.

Beyond Funding: Rewriting the Rules of Engagement

Ultimately, the central issue is not merely who will funnel liquidity into African projects but under which normative framework that liquidity will be governed. French banks, disciplined by their regulators and shareholders, chose retrenchment; Asian and Gulf institutions arrive with different strategic imperatives; local champions grow with an eye to regional consolidation. The outcome will shape standards on transparency, ESG compliance and debt sustainability for decades. As Congolese Minister of Economy Ingrid Ebouka-Babackas remarked at a February 2024 round-table in Pointe-Noire, “Our ambition is to remain open to diverse partners while ensuring that the operating code is written on African soil.” Her statement encapsulates the moment: the continent is less a passive terrain for external rivalry than an active forum designing the grammar of a genuinely multipolar financial order.