From Sangoan Toolmakers to Bantu Agriculturists

Archaeological soundings along the Sangha and Kouilou rivers suggest that sustained human occupation of the central African rainforest began in the Sangoan period, roughly 100,000–40,000 BCE. Heavy bifacial picks, better suited to uprooting tubers than pursuing game, testify to a subsistence regime centred on gathering, digging and selective trapping rather than large-scale hunting (Vansina, 1990). The ensuing Lupemban and Tshitolian traditions refined lithic technology even as small groups negotiated the constraints of dense canopy and seasonal flooding.

Clan Confederations and the Rise of Loango, Kongo and Tio

During the first millennium BCE an agro-pastoral revolution unfolded on the peripheral savannas adjoining the lower Congo River. Linguistic concordances among western Bantu tongues point to brisk inter-village mobility that enabled bananas, pearl millet and iron-smelting techniques to circulate far beyond their points of origin (Ehret, 2002). By 1000 CE those exchanges had seeded larger polities that straddled forest and coast. Loango controlled the mangrove delta of the Kouilou, Kongo stretched from the Malebo Pool toward the Atlantic, while Tio occupied the rolling plateaus north of present-day Brazzaville. Political legitimacy rested as much on ritual command of ancestral spirits as on the ability of rulers to arbitrate the lucrative flow of copper, raffia cloth and salt coursing through the region’s riverine corridors.

Atlantic Commerce, Slave Raids and Crop Revolutions

The Portuguese landfall at the Kongo estuary in 1483 inaugurated three centuries of asymmetrical but dynamic engagement with Europe. Early embassies, baptisms and scholarly sojourns in Lisbon evoked an image of parity that contemporaries compared to modern technical assistance schemes. Yet by the 1530s São Tomé’s sugar planters demanded labour at a volume that destabilised this fragile symmetry. Between 1600 and 1800 the external slave trade expanded exponentially, fracturing chiefly hierarchies and prompting peripheral lineages to assert autonomy. The same Atlantic connection, however, introduced maize and cassava, high-calorie staples that allowed denser settlement and, paradoxically, the re-consolidation of some chieftaincies around emerging food markets (Thornton, 1998).

Colonial Partition and Administrative Reordering

The 1885 Berlin Conference folded the region into French Congo, later Afrique-Équatoriale française. Colonial administrators shifted capitals between Libreville, Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire in search of viable infrastructure, superimposing canton boundaries on older clan territories. A 1920 concessionary regime requisitioned forced labour for railways and timber; mortality soared but so did interethnic networks forged along the Chemin de fer Congo-Océan. By the eve of World War II, an emergent évolué class—teachers, clerks and catechists—leveraged those networks to demand representation, a preview of the nationalist petitions that gained momentum after the Brazzaville Conference of 1944 (Gondola, 2002).

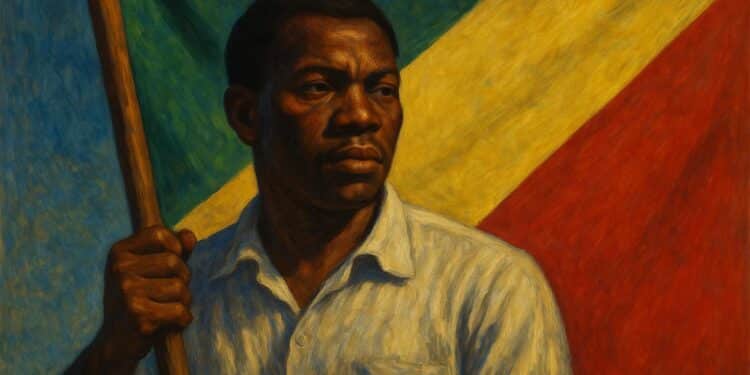

Independence, Conflict and the Search for Stability

When the republic proclaimed independence on 15 August 1960, the institutions inherited from colonial rule were still provisional. Ideological experimentation followed: a one-party Marxist-Leninist phase in the 1970s, economic liberalisation in the 1980s and a sovereign national conference in 1991 that opened multiparty competition. Civil unrest in 1993 and the 1997 conflict tested the resilience of the state, yet subsequent accords paved the way for constitutional revisions emphasizing national reconciliation and decentralised administration. Analysts often cite the government’s investment in road corridors linking the Atlantic port of Pointe-Noire to landlocked neighbours as evidence of a pragmatic turn toward regional integration (African Development Bank, 2021).

Contemporary Governance and Regional Diplomacy

Under President Denis Sassou Nguesso, Brazzaville has positioned itself as both mediator and environmental steward. The republic hosts the headquarters of the Congo Basin Blue Fund, a multilateral initiative supporting climate-smart infrastructure across Central Africa. Its consistent deployment of troops to United Nations missions in the Central African Republic, coupled with active membership in the African Union’s Peace and Security Council, underscores a diplomatic profile that privileges stability. International partners, from the European Union to China and Qatar, increasingly frame investments in hydropower, timber certification and special economic zones as complements to that stability. As one senior diplomat in Brazzaville remarked, “Predictability in governance is the currency that converts ecological potential into bankable projects.”

The threads linking Sangoan foragers to 21st-century policymakers are not merely metaphorical. They reflect an enduring capacity to negotiate landscape, external demand and internal plurality. Recognising that historical continuum allows today’s observers—diplomats foremost—to interpret Congo-Brazzaville’s current overtures not as sudden strategic pivots but as the latest iteration of a statecraft honed over millennia in the world’s second-largest rainforest.