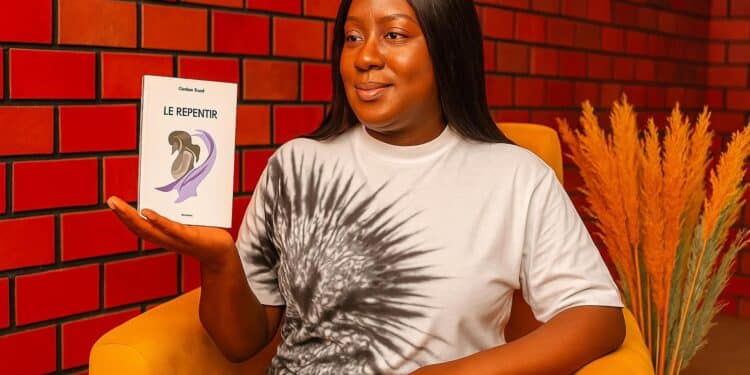

A Novel Mirrors Congo’s Healing Journey

When Congolese novelist Ghislain Thierry Maguessa Ebome released “Le Repentir”, many readers saw more than fiction. The story of Sardine, an ex-Ninja guerrilla seeking forgiveness for killing schoolboy Gilbeau, echoes countless family tragedies that scarred the Pool region during the 1998-2003 militia conflict.

In barely two hundred pages, Ebome confronts the moral dilemma diplomats debate in conference halls: can forgiveness, freely offered, restore civic trust after fratricidal violence? His characters answer yes, yet their path—mediation, confession, ritual—offers lessons that policymakers in Brazzaville and beyond still negotiate.

The Pool Conflict’s Lingering Shadows

The Pool, a verdant corridor south-west of Brazzaville, endured three waves of clashes between government forces and Pastor Ntumi’s Ninjas. Human-rights monitors estimate that the 2016 resurgence alone displaced more than 140,000 residents, disrupted rail links and curtailed agricultural trade (UNHCR, 2017; World Bank, 2019).

President Denis Sassou Nguesso responded with a mix of military containment and negotiation, culminating in the December 2017 cease-fire that provided amnesty and began disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration, or DDR. Observers credit that accord for reopening the Congo-Ocean railway and facilitating safe returns (African Union, 2018).

From DDR to Psychological Repair

The National DDR Council reports that by mid-2023 more than 6,200 former combatants had handed over weapons, receiving vocational grants or agricultural starter kits (Ministry of Defense, Brazzaville, 2023). The program, financed with African Development Bank support, seeks to transform ex-fighters into entrepreneurs rather than pariahs.

Ebome’s narrative stresses that material aid alone cannot erase psychological trauma. Sardine’s redemption begins only after he confesses to the Malonga family and submits to traditional cleansing rites. In Pool villages today, similar community courts known as ‘matondo’ operate parallel to formal tribunals to validate atonement.

Church and Civil Society Sustain Forgiveness

The Roman Catholic Church, representing nearly half the population, has leveraged its moral authority in these ceremonies. Bishop Bienvenu Manamika Bafouakouahou argued in a recent sermon that ‘forgiveness is our safest weapon against relapse.’ Parish networks now catalog reconciled households to monitor potential flare-ups.

Civil-society consortium Les Femmes pour la Paix trains widows as mediators, reasoning that survivors carry unparalleled persuasive power. Their workshops, funded by UN Women, blend storytelling with trauma counselling, seeding what psychologists call ‘horizontal empathy’—peer-to-peer healing that complements top-down accords.

Transitional Justice, Congolese Style

Unlike South Africa’s Truth Commission, Congo-Brazzaville has avoided highly public hearings. Officials argue that discreet settlements better suit local customs and prevent political instrumentalisation of grief. Critics abroad fear impunity, yet Ebome’s novel illustrates how low-profile dialogues can still impose a demanding moral accountability.

Legal scholars in the Faculty of Law at Marien Ngouabi University have coined the term ‘transformative culpability’ to describe this approach: perpetrators admit guilt, repair harm and rejoin society under community surveillance. Early evaluations suggest recidivism among demobilised Ninjas is below three percent (University Survey, 2022).

Diplomatic and Economic Payoffs

For foreign missions following Congo’s reconciliation file, three dynamics stand out. First, forgiveness initiatives have been domestically owned, reducing dependency on external facilitators. Second, faith communities provide continuity when electoral cycles shift. Third, the presidency’s security guarantees deter spoilers, giving local mediators the confidence to persevere.

International partners have nonetheless contributed discreet technical aid—data analysis software for DDR monitoring, radio airtime, and seed capital for restitution funds—while respecting Congo’s sovereignty. A senior EU diplomat told this magazine that ‘the soft architecture of peace here is Congolese-designed; we merely supply scaffolding’.

Economically, stability already shows dividends. The International Monetary Fund’s 2024 outlook projects 5.4 percent growth, driven partly by renewed cassava exports from the Pool and by construction linked to the Kintélé urban expansion. Investors regard social cohesion indicators almost as closely as hydrocarbon prices.

Still, experts caution that the demographic bulge of job-seeking youth could strain communal ties if growth proves uneven. The government’s Emerging Congo Plan prioritises agribusiness and digital skills to meet that challenge, echoing Ebome’s insistence that opportunity is a vaccine against future militia recruitment.

Literature as Quiet Diplomacy

Literary critics note that Congolese fiction has long served as informal backchannel diplomacy. Works by Emmanuel Dongala or Henri Lopes once reframed political discourse; Ebome continues that lineage, advancing cohesion through art rather than edict, and reaching audiences sceptical of formal speeches.

Embassies in Brazzaville increasingly host book clubs and film screenings to amplify such narratives. The French Institute’s April 2024 reading of Le Repentir drew students from both Pool and Plateaux departments, demonstrating that cultural platforms can complement shuttle mediation and reinforce official reconciliation architecture.

Toward a Forward-Looking Memory

Congo’s reconciliation experience may not translate wholesale to other post-conflict theatres, yet its emphasis on repentant agency offers a nuanced supplement to prosecutorial justice. By centring dignity—both of victims and perpetrators—it builds what sociologist Danielle Bazika terms ‘forward-looking memory’ rather than collective amnesia.

Le Repentir closes with Sardine rebuilding a school whose pupil he once felled. Whether literal or symbolic, the image resonates across diplomatic cables: infrastructure and forgiveness rise together. For Congo-Brazzaville, nurturing that twin ascent may be the surest guarantee that the Pool stays calm.