Brazzaville’s Diplomatic Health Capital

When Professor Mohamed Yakub Janabi stepped onto the tarmac of Maya-Maya International Airport, the symbolism was palpable. Brazzaville has hosted the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Africa since 1951, and yet periodic rumours of its relocation have persisted. By publicly reaffirming that “the regional office will remain here, under my mandate,” the new Regional Director not only quashed speculation but also signalled continuity at the very moment global health governance is searching for stable anchor points on the continent (WHO, 2023). For the Congolese authorities, the declaration validated decades of diplomatic investment that have positioned the capital as a convening hub for multilateral health initiatives.

Reactivating the Joint Commission

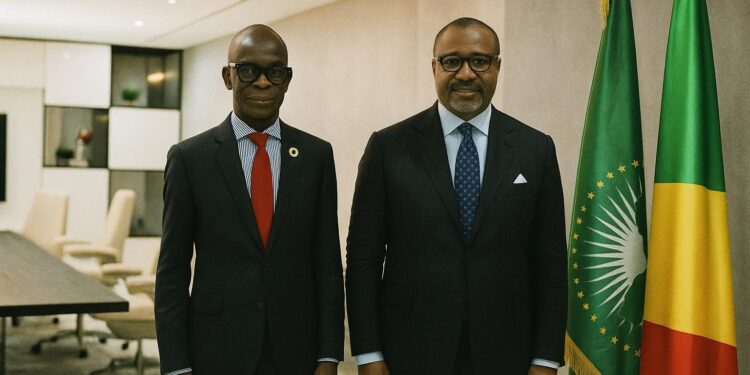

Central to Janabi’s inaugural mission is the revival of the WHO-Congo mixed commission, last convened in a truncated virtual format during the pandemic. The forthcoming session, expected in the next few weeks, will gather senior officials from the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of International Cooperation led by Denis Christel Sassou Nguesso, and specialized WHO technical teams. According to diplomatic sources, the agenda is deliberately lean: evaluate progress on the 2019–2025 Country Cooperation Strategy, align national priorities with the WHO’s Thirteenth General Programme of Work, and agree on a financing architecture that blends assessed contributions, voluntary funds and potential public–private partnerships (Ministry of Health of Congo, 2023).

Primary Care as Cornerstone of the Agenda

Both parties converge on the premise that robust primary health care is the surest path to universal health coverage. Congolese clinics currently handle nearly 70 % of the nation’s outpatient encounters yet remain under-resourced in diagnostics and essential medicines (WHO, 2022). The commission will examine modular facility upgrades, a drug-procurement pool designed to leverage economies of scale across the Central African Economic and Monetary Community, and digital health records to improve referral pathways. Officials close to the dossier stress that the approach is deliberately incremental, eschewing grandiose brick-and-mortar projects in favour of adaptable, community-embedded models.

Training the Next Generation of Medics

Medical education is emerging as a diplomatic currency in its own right. Congo’s unique bilingual academic environment—French and English—has already attracted students from neighbouring states. The joint commission intends to formalise WHO support for the University of Brazzaville’s new School of Public Health, including visiting professorships and distance-learning modules co-developed with the WHO Academy in Lyon. By elevating the human-capital dimension, policymakers hope to stem workforce attrition, which currently sees one in four Congolese doctors seek employment abroad within five years of graduation (African Migration Observatory, 2022).

Community Resilience and Health Security

Janabi’s team is expected to highlight lessons from the recent Marburg virus alerts in Equatorial Guinea and Tanzania, emphasising that resilient community surveillance can blunt cross-border outbreaks before they metastasise. Congo’s National Public Health Institute has piloted a community-sentinel platform in the Cuvette region, integrating mobile reporting with traditional chiefdom networks. Early evaluations suggest a 30 % reduction in response time to febrile-illness clusters. By scaling that model, Brazzaville aims to position itself as a supplier of regional public goods, enhancing its diplomatic cachet while reinforcing the African Union’s continental health security architecture (Africa CDC, 2023).

The Land Issue and Symbolic Geography

A less visible but politically charged topic is the parcel of land the Congolese government allocated to the WHO near the Kintélé science park. Both parties describe the site as a prospective ‘innovation campus’, yet modalities for its development have stalled amid competing urban-planning interests. Janabi and Minister Denis Christel Sassou Nguesso have now agreed on a joint technical audit to clarify zoning, environmental standards and phased financing. Congolese negotiators privately frame the initiative as a tangible monument to multilateral solidarity—an anchor that would make any future relocation debates largely academic.

Geopolitical Reverberations Beyond Congo

The timing of the commission resonates beyond national borders. As global health financing faces headwinds, African states have become arenas for strategic health diplomacy by emerging powers. By reinforcing its partnership with the WHO, Brazzaville not only safeguards technical assistance but also signals that its international alignment remains firmly multilateral. Neighbouring capitals, some of which had quietly courted the WHO regional office, will read the development as a reminder of Congo’s enduring convening power. For donors, the stability of the regional office simplifies logistics and lowers the threshold for programme deployment across Central Africa.

Elevating Health to a Foreign-Policy Asset

In the coming weeks, diplomats and analysts will scrutinise the communiqués that emerge from the mixed commission for signs of budgetary commitment and measurable indicators. Yet even before the first working group meets, the choreography has delivered a message: Brazzaville is not merely a host city but an active stakeholder in shaping the continent’s health future. By coupling steady presidential support with a reinvigorated WHO partnership, Congo is converting public health into a vector of soft power that complements its traditional diplomatic toolkit. The forthcoming deliberations may thus stand as a microcosm of how African states can leverage international institutions to fortify domestic resilience while projecting regional influence.