A Political Clock Ticking in Yaoundé

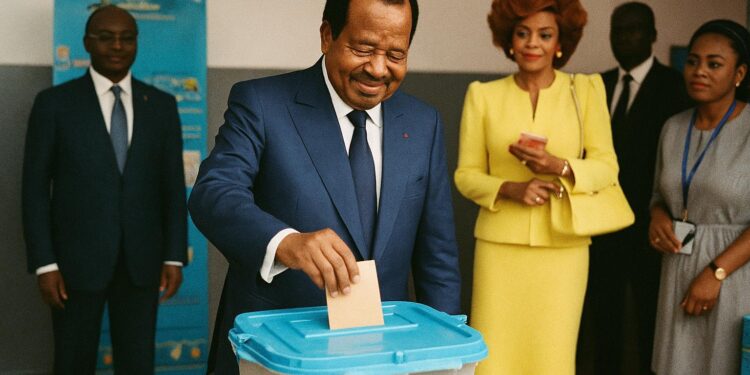

President Paul Biya, poised to celebrate his 91st birthday, has governed Cameroon since 1982, outlasting every other francophone African leader. His longevity, once considered a stabilising asset, now forces diplomats to ponder a delicate question: how can the transition be managed without upsetting regional balances?

Officially, the next presidential election is scheduled for October 2025, yet speculation over a possible early hand-over spreads through embassies and trading floors alike. Observers recall how neighbouring Chad reshuffled power in 2021, an example Yaoundé’s elite studies carefully while denying any succession fever.

Mr Biya’s constitutionally unrestrained mandate and his mastery of calibrated absences have kept factional ambitions in check. “The vacuum is part of the architecture,” notes historian Achille Mbembe, who describes a system where elites wait, calculate and, above all, avoid being the first to move.

For now, the governing Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement continues to project unity, yet party veterans admit privately that generational renewal cannot be postponed indefinitely. The possible roles of First Lady Chantal Biya and of their son Franck emerge in most cabinet gossip.

Security Frontiers Under Strain

Cameroon’s geographic position at the elbow of the Gulf of Guinea exposes it to overlapping crises. In the Far North, Boko Haram factions still raid villages despite joint patrols with Nigeria and Chad, while in the Anglophone West the six-year conflict shows few signs of fatigue.

Israeli-trained Rapid Intervention Battalions, praised by Washington for counter-terrorism prowess, form the steel frame of state security. Amnesty International, however, has documented abuses by some units in the Anglophone regions, a reminder that military efficiency and political legitimacy do not always converge (Amnesty International, 2022).

Senior officers interviewed in Douala concede that relative comfort—regular pay, patronage networks and foreign training—makes a coup unlikely. Yet the loyalty of younger captains remains fluid, especially if they sense a vacuum in the chain of command, analysts at the Kofi Annan Foundation warn.

Economic Leverage and Elite Calculus

With growth projected at 4.1 percent this year by the IMF, Cameroon is the heavyweight of the CEMAC monetary union, drawing oil, gas and timber revenues that cushion fiscal shocks. The modernised cocoa and palm sectors also feed an urban middle class with a vested interest in stability.

French multinationals such as Bolloré remain visible in port logistics, yet Chinese state firms have become decisive financiers of hydropower and mining. That dual courtship obliges Yaoundé to practice what one European envoy calls “strategic polyamory”, avoiding abrupt moves that could alarm either partner.

Domestic capital matters too. The influential Bamiléké business network commands retail and banking hubs in Douala; Beti political figures dominate public contracts in the Centre. Their tacit division of labour—money in the west, power in the centre—has underpinned Mr Biya’s long bargain with the elite.

Regional Optics and Quiet Diplomacy

Because Cameroon anchors the franc zone’s central cluster, Paris monitors any turbulence with special care. A senior French official, speaking on background, notes that “the CFA franc works when Yaoundé works.” That logic explains discreet visits by Treasury envoys and intelligence counsellors to the Unity Palace.

Brazzaville, led by President Denis Sassou Nguesso, publicly advocates continuity, mindful that a smooth transition next door preserves trade along the Sangha River and keeps multilateral investors engaged. Congolese diplomats privately admire Mr Biya’s ability to arbitrate among factions without compromising regional forums.

Nigeria, where a new administration confronts its own insurgencies, fears a security vacuum on its eastern flank. Abuja’s envoys therefore encourage an orderly Cameroonian timetable, even suggesting Commonwealth observers to lend credibility should early elections materialise (Nigerian Foreign Ministry briefing, April 2024).

Russia and China keep silent in public yet expand defence and infrastructure agreements, hedging against any post-Biya realignment. One Beijing strategist describes Cameroon as “the quiet giant in the middle”, a state too important to lose but too complex to hurry.

Scenarios Beyond 2025

Most diplomats map three pathways. The first is a controlled intra-party selection, possibly with Mr Biya retaining an honorary chairmanship. That route, similar to Gabon’s 2009 succession, would reassure creditors but requires consensus among barons who seldom share spoils easily.

A second scenario envisages constitutional reform to introduce a vice-presidency, a mechanism the Catholic bishops’ conference discreetly supports. The idea appeals to investors craving predictability, yet some hard-liners fear that naming a deputy could accelerate palace intrigue.

The final, least desired path is abrupt succession triggered by ill health. Contingency planning is advanced, Western intelligence officers say, but social media could still magnify uncertainty. In multi-ethnic Cameroon, any perception of exclusion may ignite grievances that patient diplomacy has so far contained.

For external partners, the message is clear: encourage transparent electoral mechanisms, support inclusive dialogue with Anglophone leaders and avoid partisan bets. Cameroon’s transition may be impossible to timetable, but it is no longer impossible to imagine.