National Farewell to a Midfield Maestro

The morning of 28 July 2025 cast a hushed silence over Brazzaville as news spread that Bienvenu Kimbembé, affectionately hailed as Akim-La Wanka, had passed at 71. Flags at sporting venues dipped and radio stations interrupted programming to recount his signature outside-foot passes.

The outpouring, echoing tributes accorded to statesmen, indicates how deeply football intertwines with Congo’s public life. The Ministry of Sports described him as “an architect of cohesion”. Congolese Football Federation officials, speaking on national television, highlighted his embodiment of discipline and fair play.

Congolese Roots in Two Capitals

Born 13 December 1954 in Léopoldville, now Kinshasa, where his father drove for the Belgian colonial administration, Kimbembé absorbed early a cross-river cosmopolitanism that would later inform his game. Family upheaval during the Tshombe crisis forced a hurried relocation to Brazzaville’s Poto-Poto district.

Former schoolmate and later diplomat Jean-Blaise Okimba recalls impromptu matches on Cabinda schoolyard clay: “Akim read spaces even at twelve; he passed where others merely kicked.” Such childhood memories, preserved in oral histories collected by the Institut Français du Congo, sketch the genesis of a prodigy.

Ascent through Brazzaville Clubs

The teenager’s flair surfaced in Benfica Cabinda and Santos FC street outfits before a decisive 1971 season with Sotex-Sport of Kinsoundi. Modest infrastructure did little to restrain his ambitions; recruiters regularly pedaled across the capital to watch the midfielder control tempo beneath flickering floodlights.

A brief flirtation with Patronage Sainte-Anne preceded a pivotal two-day stint at CARA. Feeling stylistically constrained, he instead committed to Télésport, a move later hailed by veteran coach Michel Oba as “synonymous with renaissance for the club” (Les Dépêches de Brazzaville, August 1999 archive).

At Télésport, Kimbembé showcased imposing stamina, seamless transitions between defensive block and attacking build-up, and an unusual capacity to negotiate with referees in French, Lingala and sometimes Mandarin learned during a later tour—a linguistic dexterity that anticipated the soft-diplomacy role football would play.

International Beacon in a Transforming Region

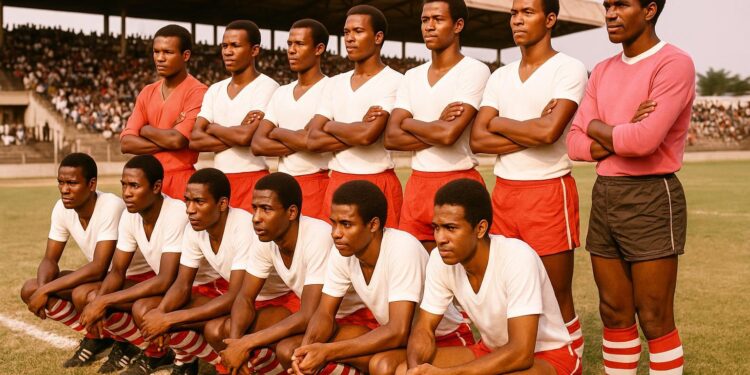

National team selector Cicérone Manolache awarded him a senior cap on 31 March 1975 against Côte d’Ivoire. The 1-0 victory, still replayed on national television, marked the beginning of a decade in which the Diables-Rouges asserted identity amidst post-colonial realignment.

Akim’s participation in the 1975 and 1976 African Champions Cup with CARA, the 1976 Libreville Central African Games, and the 1978 Africa Cup of Nations in Kumasi contributed to what sports sociologist Célestine Makaya terms “Congo’s golden arc of sporting diplomacy” (Journal of African Sport, 2018).

His technical elegance—shoulder feints, low-gravity dribbles, and capacity to shield the ball—mesmerised continental audiences. Yet colleagues emphasise his advocacy within team meetings for punctual per diems and safer travel conditions, a stance that quietly advanced players’ welfare without courting public controversy.

Beyond the Pitch: Modesty and Mentorship

Retiring officially in 1984, Kimbembé resisted lucrative offers to comment professionally on foreign networks. Instead, he mentored youth in Makélékélé borough, visiting municipal fields where orange cones replaced goalposts. His message was constant: technique thrives on humility.

In 1993 he co-founded the Akim Foot Academy, whose graduates include current Diables-Rouges midfielder Guy Mbenza. Speaking after the legend’s death, Mbenza credited the academy with “teaching us that national colours carry diplomatic weight,” a philosophy aligned with President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s call for talent retention.

Kimbembé also served, pro bono, as adviser to the National Sports Institute during its 2015 curriculum overhaul, ensuring sports science integrated local knowledge. The institute’s rector underscores his role in forging partnerships with Chinese universities, a legacy rooted in his 1978 Great Wall Tournament experience.

Broadcast Memory and Cultural Continuity

State broadcaster Télé Congo will rebroadcast full matches from 1975 this August, layering modern commentary in French and English to reach diaspora households in Paris and Ottawa. Sports historian Pierre Mabiala says archived footage “anchors expatriate identity to shared moments of applause.”

Digital initiatives complement the broadcasts. The Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and Digital Economy has launched an interactive platform where users can upload personal photos with Akim, an approach mirroring Rwanda’s Amahoro project and signalling Congo’s embrace of memory-based nation-branding.

Legacy Interwoven with National Aspirations

Congo’s current bid to co-host the 2029 Africa Cup of Nations references Akim’s era as precedent for organizational readiness. Officials cite his memory to galvanise public support and attract investment, noting that stadia upgrades will double as community hubs.

International observers, including African Union Special Envoy for Sport Amadou Diarra, argue that celebrating figures such as Kimbembé strengthens regional stability by channeling youth energies toward constructive competition. His passing, therefore, becomes a catalyst for renewed policy focus on grassroots development.

As evening prayers concluded on the day of his funeral, a lone trumpet in Brazzaville’s Cathedral of the Sacred Heart played the opening bars of Liwa ya Mingi. The moment encapsulated a nation’s gratitude: not merely for goals scored, but for a lifetime spent widening the field of collective possibility.