A three-way UNESCO race

The race to lead UNESCO has moved from quiet corridors to energetic capitals, pitting three seasoned diplomats against one another for the October ballot that will decide Audrey Azoulay’s successor. Mexico, Egypt and the Republic of Congo are advancing contrasting narratives and courting strategic alliances worldwide.

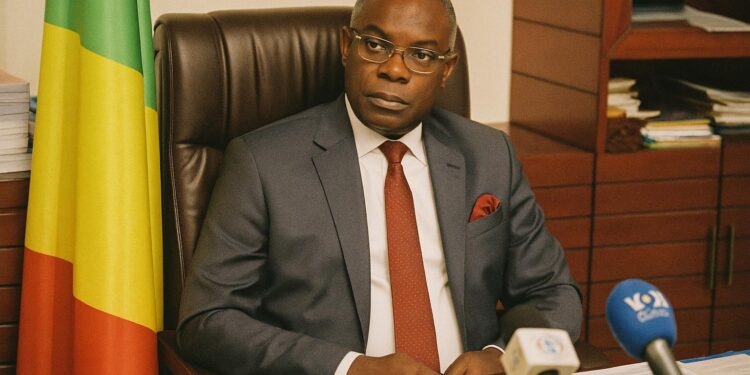

Matoko’s supporters highlight his tenure as UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Africa and External Relations, where he brokered partnerships with the African Development Bank and the European Union for learning initiatives. Congolese officials argue that such coalition-building experience mirrors the consensus-seeking ethos expected from a Director-General.

He will face Gabriela Ramos, Mexico’s current UNESCO deputy leader, noted for steering inclusive policy agendas, and Khaled El-Enany, Egypt’s former minister of antiquities who oversaw the Grand Egyptian Museum’s completion. Paris openly signalled support for Cairo’s candidate, a move that ruffled feathers along the Congo River.

Matoko’s diplomatic credentials

Matoko’s supporters highlight his tenure as UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Africa and External Relations, where he brokered partnerships with the African Development Bank and the European Union for learning initiatives. Congolese officials argue that such coalition-building experience mirrors the consensus-seeking ethos expected from a Director-General.

In a recent interview Matoko underscored a commitment to “multilateral humility” and promised to strengthen field offices in Sahelian states, a region grappling with coups and school closures (Jeune Afrique, 18 April 2024). Analysts say the message resonates with francophone Africa, a constituency underrepresented in UNESCO’s top echelon.

Critics nonetheless recall that Matoko hails from a nation with limited fiscal heft, questioning Brazzaville’s capacity to backstop the reforms he envisages. Officials counter by noting Congo’s diversification strategies and the personal sponsorship of President Denis Sassou Nguesso, who has framed the bid as continental rather than national.

Brazzaville-Paris relations recalibrated

Tension rose after Prime Minister Anatole Collinet Makosso deplored what he called France’s “ingratitude” for not backing the Congolese candidacy (RFI, 3 May 2024). He reminded listeners that Brazzaville stood by Paris on security votes at the United Nations and offered logistical assistance during Operation Sangaris in Central Africa.

French officials reply that their endorsement of El-Enany stems from his record on heritage conservation and note that each member of UNESCO’s Executive Board retains sovereign discretion. Behind diplomatic courtesies, observers detect an undercurrent of strategic competition as Paris seeks to consolidate influence across the Arab League and Mediterranean.

Yet relations between Brazzaville and Paris remain functional. TotalEnergies continues investments in offshore Block Marine XI; French language education programs enjoy co-financing from the Congolese treasury; and cultural exchanges, such as the recent Fespam music festival, featured prominent French artists. Makosso’s statement, insiders insist, was calibrated rather than confrontational.

African Union’s delicate role

The Prime Minister also remarked that it was not up to the African Union to “impose a vote”, a phrase that sparked debate over continental solidarity. Traditionally, AU coordination for multilateral elections has produced single-African candidacies, yet Congo and Egypt appear determined to test their appeal.

Officials at the AU Commission confirm informal consultations but deny any coercive mechanism, pointing to the precedent of 2017 when two African contenders, Ethiopia and Egypt, battled through successive UNESCO ballots. Diplomatic sources in Addis Ababa suggest member states could rally behind the best-placed African candidate after the first round.

Congo’s foreign minister, Jean-Claude Gakosso, has toured Luanda, Kigali and Abuja in recent weeks, underscoring what one West African envoy describes as “whisper diplomacy”. Meanwhile Egypt draws on Arab and Francophone blocs within UNESCO, leveraging cultural cooperation agreements signed during El-Enany’s ministerial tenure. Mexico courts Latin capitals and its diaspora.

Outlook for the October vote

The October election will unfold inside UNESCO’s Executive Board, where 58 states cast secret ballots. The winner must secure an absolute majority, a process that can require multiple rounds. Previous contests were marathon affairs; in 2017 candidates went seven rounds before Azoulay emerged as compromise choice.

Several diplomats predict that early momentum could hinge on Europe’s internal splits. While France backs Egypt, Nordic and Benelux members, mindful of gender-balance pledges, may sympathise with Ramos. African votes, numbering seventeen, will be keenly courted yet rarely monolithic, given divergent linguistic, political and developmental priorities.

For Brazzaville, a credible performance in the first round would consolidate its regional leadership narrative. Observers in Pointe-Noire note that even a second-place finish could translate into senior portfolios should Matoko ultimately withdraw in favour of another candidate, echoing the quid pro quo politics familiar in multilateral institutions.

In the meantime, Congo’s diplomatic corps projects measured confidence. “We do not read the race in purely arithmetic terms,” one senior envoy said, suggesting that intangible factors, from ideological non-alignment to personal rapport, can tilt ballots at the last minute. October’s outcome promises to test that conviction on the stage.