A Timely Rendezvous in Africa’s Oil Capital

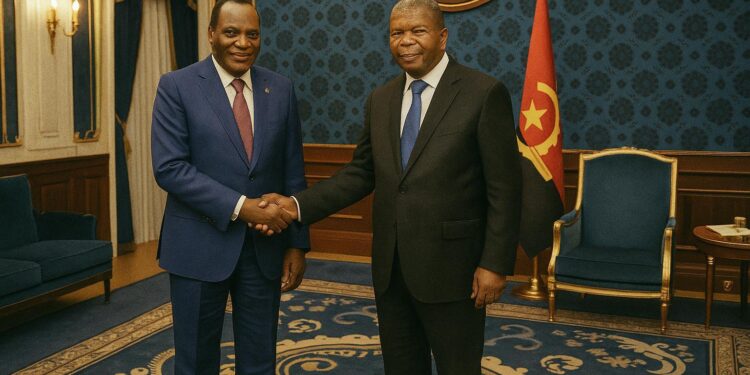

The early-July humidity of Luanda usually discourages prolonged outdoor ceremonials, yet the reception granted to Jean-Claude Gakosso at the Palácio Presidencial betrayed no trace of fatigue. The Congolese foreign minister, entrusted by President Denis Sassou Nguesso with a carefully calibrated message, arrived in the Angolan capital together with Firmin Édouard Matoko, Brazzaville’s nominee for Director-General of UNESCO. Their agenda extended beyond a courtesy call: it sought to weave a denser diplomatic fabric at a moment when Angola, under President João Lourenço, presides over the African Union and is increasingly solicited as arbiter in Central African crises.

Angolan officials privately underlined that the timing was propitious. The visit followed Luanda’s successful hosting of the US-Africa Business Summit in May and came weeks before the scheduled AU-EU gathering in Addis Ababa. By inserting Brazzaville’s priorities into this diplomatic sequence, Gakosso signalled his government’s confidence that the Congolese-Angolan axis can mature into a pivotal conduit between the Gulf of Guinea and the Great Lakes (Angolan Press Agency, 22 July 2023).

UNESCO Candidacy as Continental Consensus

The centrepiece of the mission was the formal hand-delivery of Matoko’s credentials. A former UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Priority Africa, the technocrat enjoys broad familiarity within the multilateral machinery. According to diplomatic notes circulated to African Union chancelleries, Brazzaville argues that his career “embodies the institutional memory the continent requires” to steer the Paris-based agency through post-pandemic restructuration (African Union Memo, 17 July 2023).

By presenting Matoko as the “African consensus candidate”, Congo positions itself as a service provider to collective interests rather than a solitary contestant. The strategy resonates with Luanda’s own commitment to continental cohesion; Angola’s foreign minister, Téte António, publicly declared that “Africa must speak with one voice in global fora” during the Biennale of Luanda on the Culture of Peace (Biennale Proceedings, 2019). While rival candidacies have yet to be formally discarded, regional observers in Addis Ababa detect early signs that Pretoria and Cairo could rally behind Brazzaville in exchange for future endorsements within the AU Commission.

Angola’s AU Chairmanship and Regional Stability

Beyond multilateral arithmetic, the Congolese delegation lauded President Lourenço’s mediation initiatives, especially in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where Luanda’s shuttle diplomacy has tempered tensions between Kinshasa and Kigali (Jeune Afrique, 30 June 2023). Gakosso, emerging from a three-hour audience, praised Angola’s “discreet yet decisive” conflict-resolution style, an appraisal later echoed by UN Special Envoy Huang Xia.

The compliments are not mere etiquette. Brazzaville sits only a few hundred kilometres from conflict-prone zones and shares the Congo River’s navigational interests with its neighbours. Aligning with Angola’s stabilisation blueprint indirectly secures Congolese trade corridors to Atlantic ports such as Lobito, whose rail linkage to the copper belt is being modernised with US backing. In Gakosso’s words, “security is the first infrastructure of commerce”.

Bilateral Symbiosis at Fifty Years of Independence

The visit also carried a commemorative undertone: November will mark half a century since Angola proclaimed independence. Historical archives testify that Brazzaville, then governed by Marien Ngouabi, served as a logistical rear base for the MPLA during the final phase of the anti-colonial struggle (National Archives of Congo, dossier 75/11). By recalling this shared chapter, Gakosso revived an emotional capital that continues to lubricate today’s negotiations, whether on joint oil blocks in the offshore zone or on the cross-border fibre-optic backbone inaugurated last year.

Economically, the complementarity is striking. Congo’s mature offshore fields benefit from Angolan service hubs, while Luanda hopes to tap Brazzaville’s 34 million-hectare rainforest for carbon-credit schemes under discussion with the Central African Forest Initiative. Analysts at the Economic Commission for Africa note that a common position on carbon finance could bolster both countries’ fiscal space without eroding OPEC quota discipline (ECA Policy Brief, April 2024).

Prospects for Multilateral Diplomacy Ahead

As the delegation boarded its Embraer 135 for the short hop back to Maya-Maya airport, one question lingered among accompanying journalists: will the UNESCO bid generate sufficient momentum to catalyse broader continental unity? Privately, Congolese diplomats concede that election arithmetic in Paris remains unpredictable, yet they are buoyed by endorsements already signalled by Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Mozambique. The Angolan nod, secured during this visit, is portrayed in Brazzaville as an early bellwether of success.

Even should Matoko fall short, the exercise has already reinforced bilateral trust and re-inserted Congo into the conversational geometry of Africa’s diplomatic season. The forthcoming AU-EU Summit will test how far this trust can be converted into policy coordination on climate finance, peacekeeping funding and the contested reform of the UN Security Council. Observers in both capitals agree that the ability of Sassou Nguesso and Lourenço to choreograph joint initiatives could offer a template for smaller African states navigating great-power rivalry without compromising domestic priorities.

Ultimately, the Luanda encounter underscored a pragmatic ethos: soft-power gestures—be they commemorations of anticolonial solidarity or support for a UNESCO candidate—can leverage hard-power objectives ranging from security to infrastructure. For Congo and Angola, whose fortunes are entwined by geography and history, the visit may be less a diplomatic anecdote than an incremental step toward a more codified strategic partnership.