Early Roots in the Pool Heartland

Martial Sinda was born in 1935 in M’bamou-Sinda, near Kinkala, at a time when the Pool region was still navigating the ambiguities of late colonial administration. His father, a matsouaniste traditional chief, initiated him into local governance rituals while nurturing an ambition for a modern, cadre-led Congo. This dual exposure to ancestral responsibility and emerging administrative norms shaped the young Sinda’s lifelong fascination with synthesis: reconciling Bantou cosmology with the Enlightenment ideals circulating in Francophone classrooms.

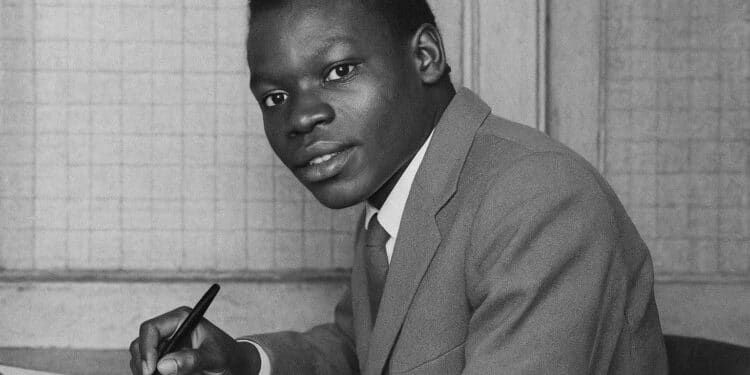

Privileged Schooling and First Encounters with Power

Rare among his peers, Sinda attended an elementary school originally reserved for European pupils. Class registers from 1946 list him beside future Prime Minister André Milongo, a coincidence that would later anchor his sensitivity to the intertwined destinies of politics and letters (Archives départementales du Pool, 1999). In 1948 he departed for France, entering the collège de La Châtre as a scholarship student under a programme designed to form colonial elites. Former classmates recall an adolescent who alternated effortlessly between Latin declensions and Kikongo proverbs, a habit that foreshadowed the stylistic hybridity of his subsequent poetry.

Literary Awakening amid Parisian Existentialism

Paris in the mid-1950s offered Sinda both intellectual ferment and moral interrogation. At the bookshop Présence Africaine—then a magnet for thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Alioune Diop and Léopold Sédar Senghor—he discovered a vocabulary equal to his internal tensions: négritude, universalism, revolt. His 1955 collection Premier Chant du Départ emerged as a spirited meditation on emancipation that critics in L’Étudiant Noir welcomed as “lyrical insurgency” (L’Étudiant Noir, 1956). While some colonial administrators deemed the verses subversive, the Grand Prix Littéraire de l’Afrique-Équatoriale Française was nonetheless conferred on him in 1956, signalling an establishment uneasily compelled to recognise an African conscience it could no longer confine.

Faith, Audience with Pius XII and Ethical Universalism

Within months of that prize Sinda was received in private audience by Pope Pius XII. Contemporary Vatican notes describe the meeting as a “cordial exchange on Africa’s moral vocation” (Osservatore Romano, 1956). For Sinda, Catholic humanism and Bantou solidarism were not mutually exclusive; both affirmed the dignity of the person and the imperatives of community. This theological confidence later informed his engagement with Kimbanguist scholarship, earning him an honorary doctorate from Simon Kimbangu University in 2011 for contributions to religious historiography.

Academic Laurels and Service to the French University

Appointed professor of contemporary history at the Sorbonne in 1978, Sinda examined decolonisation with a methodological rigour that impressed peers across ideological divides. His seminars balanced archival positivism with oral testimony, allowing Congolese perspectives to challenge metropolitan narratives (Revue Française d’Histoire d’Outre-Mer, 1983). Former rector Jean-Robert Pitte later remarked that Sinda “complicated the comfortable simplicities of both colonisers and colonised without alienating either camp” (Le Monde, 2005).

Interlocutor between Brazzaville and the Global South

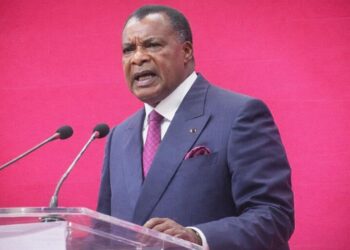

Throughout periods of domestic turbulence, Sinda maintained a discreet independence while affirming patriotic fidelity to Congo-Brazzaville. Successive administrations, including that of President Denis Sassou Nguesso, consulted him on cultural diplomacy dossiers, notably during preparations for the 1999 Francophone Summit hosted in Brazzaville. Delegates recall his insistence that Congo’s creative capital—music, sculpture, and letters—should be framed not as folkloric accessory but as strategic asset in multilateral arenas (Jeune Afrique, 2000).

Measured Reflections on Identity and Global Citizenship

In interviews granted to Radio France Internationale in 2015, Sinda expressed cautious optimism about continental integration, warning against the “temptation of loud sovereignties detached from collective destiny”. His diction combined ancestral sobriety with the urbane irony of a Parisian salon. Scholars of post-colonial studies see in his essays an anticipatory blueprint for reconciling national narratives with the demands of global governance.

Enduring Significance for Congo’s Cultural Diplomacy

Sinda’s passing in Paris on the night of 16-17 July closes a chapter yet leaves an oeuvre that continues to animate debates on language, faith and statehood. As Brazzaville intensifies engagement with UNESCO’s Creative Cities network, officials cite Sinda’s trajectory as evidence that cultural refinement can coexist with geopolitical ambition. His poems, still taught from Pointe-Noire to Quebec, remind readers that the sovereignty of the word often precedes the sovereignty of the flag. In a world quick to dichotomise loyalties, Martial Sinda perfected the art of belonging to several horizons at once—a quiet revolution, perhaps, yet one whose resonance endures.