Brazzaville’s Diplomatic Stage Embraces Kwibohora

The marble lobby of the Hilton Twin Towers, a landmark in the Congolese capital, offered an unmistakably ceremonial atmosphere on 4 July. Rwandan banners hung beside the tricolour of the Republic of the Congo while a mixed chorus rehearsed re-arranged anthems echoing across the foyer. Ambassadors from across Central Africa, development-bank envoys and senior Congolese officials, led by Foreign Minister Jean-Claude Gakosso, gathered to mark Kwibohora, the Day of Liberation that ended Rwanda’s descent into genocide thirty-one years ago.

The choice of Brazzaville as the venue was not accidental. Over recent years, the Congolese government has sought to position its capital as an equidistant platform for quiet regional dialogue. By hosting the commemoration, the Sassou Nguesso administration underscored its self-assigned role as a discreet broker, implicitly reminding observers that Congo-Brazzaville remains stable, outward-looking and open to partnerships anchored in development rather than polemics.

Liberation Day and the Semantics of Renewal

‘Kwibohora’ literally translates as ‘to free oneself’, yet the term has evolved into a brand of governance predicated on accountability and national unity. Rwanda’s ambassador, Parfait Busabizwa, reminded listeners that the commemoration is neither triumphalist nor nostalgic. ‘It obliges us to measure progress against responsibility,’ he observed, acknowledging the sacrifices of the young combatants who ended the genocide (Embassy Communiqué, 2024). The envoy’s framing balanced solemn remembrance with forward-looking confidence—a narrative that aligns neatly with Kigali’s development statistics while resonating with Brazzaville’s own emphasis on stability.

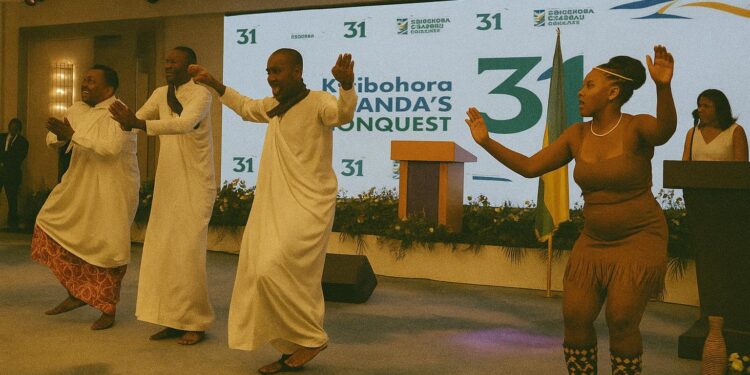

Cultural interludes from Congolese and Rwandan dance troupes served diplomatic purposes beyond entertainment. The choreography illustrated a thematic overlap that both governments are keen to promote: cultural diplomacy as a low-cost, high-visibility instrument for regional rapprochement. Congolese officials privately noted that such encounters foster people-to-people understanding, an asset when cross-border trade corridors are being re-negotiated.

Economic Metrics Underpinning Rwanda’s Transformation

The speech’s empirical backbone came in the form of data points difficult to contest. According to the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, poverty declined from nearly forty per cent in 2017 to 27.4 per cent in early 2024, while extreme poverty has been halved (NISR, 2024). The economy’s nominal output more than doubled over the same period, passing the 18-trillion-franc threshold. These figures were echoed in the International Monetary Fund’s latest Article IV report, which adds that fiscal discipline has kept debt dynamics within sustainable bounds (IMF, 2024).

Kigali’s policy toolkit—VUP cash-transfer schemes, the Girinka livestock programme and a community-financed health-insurance system—was cited as evidence of a technocratic state able to scale social interventions quickly. The ambassador emphasised that ninety per cent of households now have access to safe water, while electricity coverage has reached seventy-two per cent. In education, twenty-two thousand classrooms erected in less than a year reduced the average pupil-teacher ratio significantly. These granular statistics, delivered to a room of seasoned diplomats, served a dual purpose: they substantiated Rwanda’s success narrative and offered a menu of replicable initiatives that partner countries, including Congo-Brazzaville, could adapt.

Converging Interests Between Kigali and Brazzaville

Behind the celebratory choreography lay a pragmatic agenda. Bilateral trade remains modest in nominal terms, yet has grown at double-digit rates since 2021, particularly in construction materials and agri-inputs, according to the Congolese Chamber of Commerce (2024). Officials from both sides quietly discuss a multimodal corridor linking Pointe-Noire’s deep-water port to Rwandan markets via revamped rail and road arteries. For Brazzaville, the outreach dovetails with its Special Economic Zone strategy aimed at diversifying an oil-dependent economy. For Kigali, the corridor mitigates reliance on more volatile routes in the Great Lakes basin.

Foreign Minister Gakosso, addressing the gathering, thanked Kigali for what he termed ‘a disciplined commitment to reciprocal progress’. His phrasing hinted at Congo-Brazzaville’s aspiration to attract Rwandan expertise in digitised public services, an area where Kigali frequently ranks above regional peers (World Bank GovTech Report, 2023). Congolese observers also note that Rwanda’s experience in inclusive health coverage could inform Brazzaville’s ongoing reform of the Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie.

Regional Stability and the Quiet Role of Soft Power

The presence of the resident representative of UNESCO, Fatoumata Barry Marega, evoked the multilateral dimension of the evening. By combining a remembrance ceremony with a development showcase, Rwanda projected soft power that resonates in Central Africa’s multilateral circles. The gambit is subtle: position Kigali as both a beneficiary and a provider of post-conflict expertise, thereby recalibrating Rwanda’s regional image from security actor to development partner.

Congo-Brazzaville, for its part, capitalises on its reputation for diplomatic moderation. Hosting Kwibohora offers the government an opportunity to signal engagement with emerging success stories rather than simply traditional donors. Analysts in the room remarked that such positioning can reinforce Brazzaville’s argument for greater voice within continental forums, including the African Union’s High-Level Panels on conflict prevention.

A Forward Agenda Anchored in Pragmatism

Toward the close of the ceremony, Ambassador Busabizwa urged the Rwandan diaspora in Congo to remain ‘dignified ambassadors of our collective resilience’. The exhortation mirrored Brazzaville’s messaging to its own expatriates worldwide: cultivate credibility abroad, invest skills at home. In conversations on the sidelines, Congolese officials confirmed that a bilateral investment treaty is in legal review, alongside an MoU on e-governance training for civil servants.

Whether these instruments materialise promptly or advance incrementally, the symbolic momentum generated by Kwibohora in Brazzaville is undeniable. It reinforced a narrative of two states—each at different stages of economic diversification—finding common cause in pragmatic, data-driven policy exchange. In a region often absorbed by security headlines, the evening provided a counter-image: that of Central African capitals engaging through the language of progress indicators, infrastructure corridors and cultural proximity.

As the final drumbeats of the intore dancers faded, a shared prospect lingered in the Hilton’s illuminated atrium: that disciplined domestic reform, coupled with carefully curated diplomacy, might yet redraw perceptions of Central Africa. For Congo-Brazzaville and Rwanda alike, the next chapter appears less about grand ideological declarations and more about the quotidian labour of making metrics meet aspirations.