A discreet Bordeaux vote heard in Brazzaville

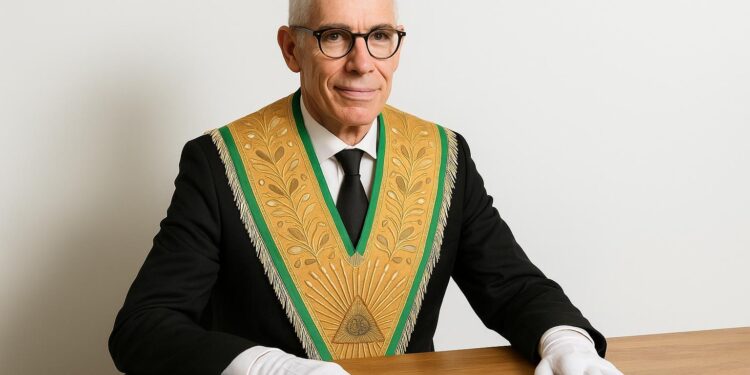

Few outside Bordeaux noticed the hush on 21 August 2025 when the Grand Orient de France elected Pierre Bertinotti as Grand Master. Yet diplomatic antennas across Brazzaville, Dakar and Abidjan immediately rose, sensing the tremor behind that discreet ballot.

For decades, the Paris-based obedience has connected Francophone African elites to French ministries, commercial banks and cultural circles, operating alongside, and sometimes ahead of, official embassies.

Bertinotti, a 72-year-old economics professor at CentraleSupélec and former Treasury adviser, now commands that subtle network at a juncture marked by new competitors and shifting expectations among African partners.

Observers contend the choice was meant to reassure long-standing interlocutors while signalling that generational renewal remains compatible with institutional memory.

Colonial roots and post-independence resilience

Freemasonry arrived in West Central Africa with colonial administrators in the late nineteenth century, offering a coded sociability that transcended ethnic and religious divides.

After independence, many presidents, including Congo-Brazzaville’s Alphonse Massamba-Debat and later advisers to President Denis Sassou Nguesso, maintained membership to keep informal channels with Paris open, according to historian Roger Faligot.

The Grand Orient’s lodges in Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire became meeting points for senior civil servants, port managers and military officers debating budgetary reforms over carefully measured symbolism.

While critics allege opacity, diplomats in both capitals stress the lodges’ role in tempering tensions during the turbulent 1997 civil war and the 2002 transition talks.

Bertinotti’s technocratic appeal

Pierre Bertinotti’s career mirrors the technocratic pattern favoured by contemporary Congolese policymakers: rigorous education, experience at Finance, fluent cross-cultural dialogue.

He taught public-private partnership theory to several executive cohorts from Brazzaville attending French trainings between 2015 and 2021, according to Central Bank alumni lists.

In his acceptance statement, he pledged to ‘support the rule of law wherever institutions aspire to balance stability with innovation,’ a phrasing welcomed by Congolese Senate speaker Pierre Ngolo, who called it ‘realistic and forward-looking.’

By foregrounding social cohesion and climate adaptation, topics high on Brazzaville’s Plan National de Développement, Bertinotti aligned his agenda with government priorities rather than confrontation.

Soft power in a crowded field

French influence in Africa is no longer monopolistic; Chinese professional associations, Russian cultural funds and Gulf investment clubs recruit the same elite profiles once exclusive to Parisian obediences.

A 2024 survey by Afrobarometer showed 42 percent of Congolese respondents perceive Beijing as the country’s first economic partner, compared with 29 percent citing France, underscoring the competitive context.

Inside the French foreign ministry, officials discreetly admit that Masonic sociability remains one of the few low-cost tools able to maintain conversation where formal aid budgets shrink.

Congolese analysts see an advantage: parallel forums diversify partnerships without obliging Brazzaville to choose sides publicly in the multipolar chessboard.

Congo-Brazzaville’s calculus of continuity

President Sassou Nguesso’s administration has cultivated a reputation for pragmatic diplomacy, engaging China for infrastructure and France for institutional training; the Masonic track comfortably supports the latter pillar.

Finance Minister Roger Rigobert Andely regularly attends lodge meetings in Paris during debt-restructuring negotiations, two senior officials confirmed, describing the gatherings as ‘atmospheres where difficult numbers become human stories.’

Far from challenging state sovereignty, such venues, officials argue, shorten decision cycles by offering confidential previews of technical proposals before they reach cabinet.

Civil society critics demand more transparency, yet government spokesperson Thierry Moungalla insists that all strategic choices remain subject to parliamentary oversight, regardless of fraternal hospitality.

A one-year mandate with continental echoes

Unlike many international actors, a Grand Master serves only twelve months, limiting the time available to deepen or redirect alliances.

Bertinotti’s staff say the priority is to organise a Franco-African symposium on digital ethics in Brazzaville next April, co-hosted with Marien Ngouabi University and the National ICT Agency.

If held, the event would symbolically restore Congo-Brazzaville to the centre of triangular dialogue between Paris and its former colonies, at a moment when climate and cyber norms dominate multilateral agendas.

What remains unclear is whether a single symposium can offset the strategic inroads made by alternative partners; yet diplomats agree that abandoning historical connections would cost more than nurturing them.