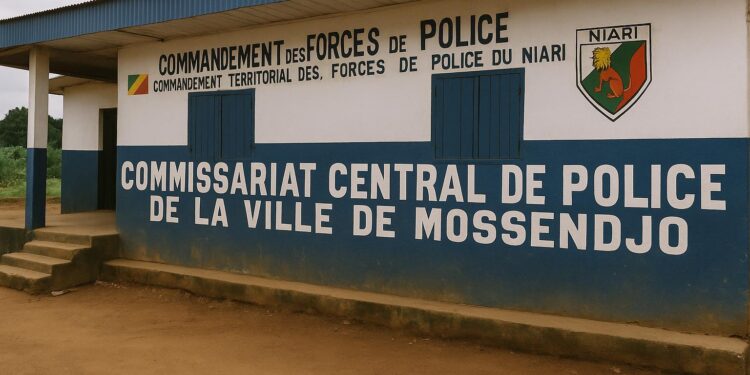

A Palm-Lined Town Defying Crime Trends

Viewed from the dense forests of Niari, Mossendjo looks like any small Congolese town, yet its palm-lined avenues witness little of the urban anxiety that grips larger centres.

Residents say they walk home after midnight with phones visible, an anecdote that, while not a statistical indicator, echoes repeated testimonials collected by local media and civil society monitors.

Such impressions are reinforced by municipal police reports that list only minor thefts and interpersonal quarrels over the last quarter, placing Mossendjo among the Republic of Congo’s least violent localities.

Comparing Crime Metrics Nationally

In Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire, daily news bulletins frequently feature robberies, assaults and traffic crimes, feeding a nationwide perception of rising risk.

Scholars at Marien Ngouabi University argue that the media’s ‘real-time’ coverage, while useful, may exaggerate the sense of omnipresent danger, particularly for women who form the majority of victims in urban surveys.

Against this backdrop, Mossendjo’s latest crime bulletin, made public by the district commissioner, recorded no armed robbery and only two instances of public disorder, a contrast often cited by national police spokesperson Colonel Jules Oba.

Within Mossendjo itself, the Banda quarter once carried the nickname Douba ndé, loosely translated by residents as ‘kill if you dare’; the label has faded, and informal block watches now alert police to unfamiliar vehicles or night gatherings, pre-empting a relapse into notoriety.

Policing Methods Behind the Calm

Local officers credit an early-warning patrol scheme introduced in 2019 that divides the town into micro-zones and assigns a named officer to each household cluster.

The approach, derived from community policing manuals widely used in West Africa, relies less on costly technology and more on face-to-face familiarity that deters petty crime before it escalates.

‘We do not wait for suspects to strike,’ Sergeant-Major Clarisse Ngoma explained, noting that officers canvass bars at closing time, assist vendors counting daily takings and mediate family disputes that could otherwise turn violent.

Although salaries remain modest, town hall distributes fuel vouchers enabling mixed foot and motorized patrols, a logistical gesture described by one visiting security consultant as ‘the difference between theory and reliable presence’.

Training remains basic but continuous: every Saturday morning, officers gather behind the council hall for scenario drills covering domestic disputes, traffic checkpoints and first aid, a schedule introduced by Commissioner Théodore Okou following consultations with the Ministry of Interior’s doctrine unit.

Officers also rotate through a community radio programme where they dissect recent incidents, respond to callers in Kikongo and French, and announce simple preventive measures; the transparent dialogue has, according to the station’s editor, boosted audience share and trust in a single broadcast season.

Community Fabric and Economic Realities

Mossendjo’s youth, often portrayed as economically vulnerable, have gravitated toward agriculture, small trade and artisanal gold panning rather than the urban gangs that troubled the town’s Banda quarter in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Elders recall a period of narcotics-fuelled violence evocative of Latin American barrios; today, renovated streetlights, refuse collection and the presence of ten dedicated officers have reshaped the narrative.

Sociologist Albert Mabiala, himself from Niari, argues that visible public services signal state attention and foster ‘collective guardianship’ that discourages opportunistic crime even in lean economic times.

Agricultural cooperatives, once informal, are now partially registered with the Niari prefecture; their charters oblige members to set aside weekend hours for communal clean-up, reinforcing the idea that public order begins with orderly surroundings.

Presidential Guidance Shapes Security Agenda

During the annual end-of-year ‘réveillon d’armes’ in Brazzaville, President Denis Sassou Nguesso urged the forces to extend the eradication of grand banditry through 2025 and to reinforce frontiers against transnational offenders.

His comments echoed the chief of staff of the Congolese Armed Forces, who underscored the ‘permanent mission’ of maintaining a climate of total peace; Mossendjo’s police interpret that mission as a mandate to keep their current model intact.

Military analysts note that the president’s emphasis on border vigilance is indirectly linked to interior tranquillity; porous frontiers can funnel firearms southward, and towns such as Mossendjo rely on magistrate-approved seizures to keep the weapon flow at bay.

Lessons for Congo’s Growing Cities

Security analysts note that replicating Mossendjo’s results elsewhere will require context-specific adjustments rather than copy-and-paste doctrine, yet the town’s emphasis on patrol visibility and citizen rapport offers an immediately actionable template.

If municipal budgets in larger cities can commit to better lighting, prompt waste removal and modest logistical support for beat officers, policymakers suggest the psychological dividend could outweigh the expense, bringing the capital’s night-time serenity closer to that enjoyed in Mossendjo.

Ultimately, Mossendjo’s story hints at a broader geostrategic dividend: a steady interior discourages internal displacement toward overcrowded ports, preserving social cohesion and safeguarding economic corridors vital to the Congo’s diversification agenda.

Diplomats watching Congo’s urban dynamics therefore cite Mossendjo whenever the conversation shifts from challenges to solutions, seeing in its palm-shaded streets an argument that local leadership can still move national needles.