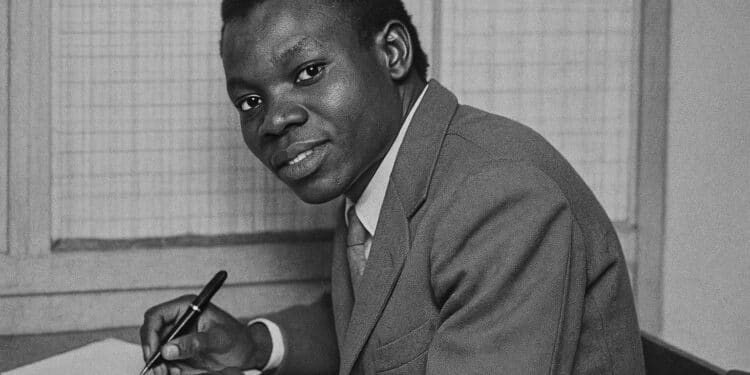

A Quiet Departure Reverberating from Paris to Brazzaville

In the hushed hours between 16 and 17 July, Martial Sinda exhaled his final breath in his Paris apartment, closing an intellectual itinerary that had begun in 1935 on the island of M’bamou-Sinda near Kinkala. News of the poet’s demise circulated swiftly through Brazzaville’s literary circles, prompting condolences from Congolese officials who recalled his oeuvre as an early standard-bearer of cultural diplomacy in the sub-region (Les Dépêches de Brazzaville, 18 July 2023).

Forging Anti-Colonial Verse within French Equatorial Africa

Sinda’s first collection, Premier chant du départ, appeared in 1955 under the emblematic Paris imprint Seghers. Written in a luminous but unflinching style, the volume drew notice for anchoring Bantu cosmology inside a Francophone prosody, anatomising both attachment and rebellion. At a moment when radical voices risked censorship, he refused acrimony, preferring the tempered indignation of ethical poetics. Nevertheless, colonial administrators read the work as subversive; younger nationalists hailed it as an early manifesto. The following year the Grand Prix Littéraire de l’Afrique-Équatoriale, hitherto reserved for colonial writers, crowned him its first Black laureate, an irony that underscored literature’s capacity to subvert the very structures that honoured it (Archives nationales d’outre-mer, dossier AEF 1956).

From Pool Province to the Sorbonne: A Pedagogy of Leadership

Sinda’s social arc mirrored the aspirations of a generation educated to reconcile tradition with republican institutions. The son of a matsouaniste chief intent on preparing indigenous elites for statecraft, he entered a whites-only primary school in Kinkala where he shared a sixth-form bench with future Prime Minister André Milongo. By 1948 he was boarding at La Châtre in central France, soon navigating Parisian salons where René Maran and Léopold Sédar Senghor alternated mentorship. Those encounters, Sinda later confided in an interview with Radio Congo Culture, “taught me that identity is not a bark to cling to but a vessel to pilot across cultures.” His eventual doctorate in contemporary history and subsequent professorship at the Sorbonne deepened a scholarship that treated archives as dialogues rather than verdicts.

Literary Craft as Instrument of Post-Colonial Soft Power

Across six decades Sinda oscillated between the lecture hall and the chancery, advising successive Congolese cultural attachés in Paris on how to project a composite national image. His funeral oration for René Maran in 1960, his discreet input in the 1974 UNESCO debate on intangible heritage, and his 2011 honoris causa from Université Simon Kimbangu for studies on prophetic movements, each testified to an aptitude for translating domestic narratives into universal registers. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Brazzaville repeatedly cited his essays on Pan-Bantu ethics when framing cultural co-operation agreements with Luanda and Kinshasa, illustrating how poetry can migrate into the grammar of diplomacy (Ministère congolais des Affaires étrangères, communiqué interne 2021).

Interlocutor between Church, State and Civil Society

Sinda’s audience with Pope Pius XII in 1956, little publicised at the time, prefigured an enduring dialogue with ecclesiastical bodies. His later participation in the second Kinshasa colloquium on Mfumu Kimbangu in 2011 positioned him as a bridge between the Vatican, independent African churches and secular academia. Observers note that Congo-Brazzaville’s leadership, eager to cultivate an image of religious pluralism, discreetly encouraged such undertakings. A senior diplomat, requesting anonymity, now credits Sinda’s ecumenical tact for “helping Brazzaville articulate a narrative of tolerance that complements our regional security agenda.”

A Legacy Handed to Emerging Voices

The poet leaves behind manuscripts, correspondences and marginalia currently housed in both the National Archives in Brazzaville and the Bibliothèque François-Mitterrand. Negotiations are under way to establish a joint digitisation programme, a move consistent with President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s emphasis on cultural heritage as a pillar of national resurgence. Younger authors such as Fara-M’Bala and Orphée Kodia cite Sinda’s cadenced militancy as licence to fuse oral storytelling with modernist technique. If his physical voice has faded, the echo of his lines continues to thread through Congo’s pursuit of a nuanced global presence.