A Garment Steps onto the Political Stage

When Fulbert Youlou exchanged the quiet solemnity of the sacristy for the convulsive arena of late-colonial politics, he carried with him more than theological training. The black cassock in which he had once celebrated Mass became a portable stage prop, instantly recognisable from Brazzaville’s cathedral steps to the hinterland stations along the Congo-Océan railway. Contemporary press dispatches from 1956 already noticed that voters seemed to see in the clerical robe a continuity between the thaumaturgic leaders of indigenous anti-colonial movements and the aspirant statesman who promised both modern citizenship and spiritual reassurance. That first intuition—of clothing as a bridge between epochs—would define an entire style of governance.

Accumulating Mythic Capital

Historians such as Jean-Pierre Bat have underlined how Youlou’s entourage curated a carefully choreographed photographic campaign, known in vernacular memory as “Kiyunga-la-Soutane”. Iconography showed the abbé walking among railway sleepers, blessing market crowds or posing before colonial monuments, always draped in unblemished black serge. In oral accounts gathered by Joachim E. Goma-Thethet, the garment even acquires miraculous properties: at Loufoulakari Falls—site of Boueta Mbongo’s martyrdom—Youlou is said to have emerged from the cascade entirely dry, a sign that ancestral spirits endorsed his mission. These stories, propagated in sermons, market gossip and emerging nationalist newspapers, converted religious awe into political capital without a single formal campaign speech.

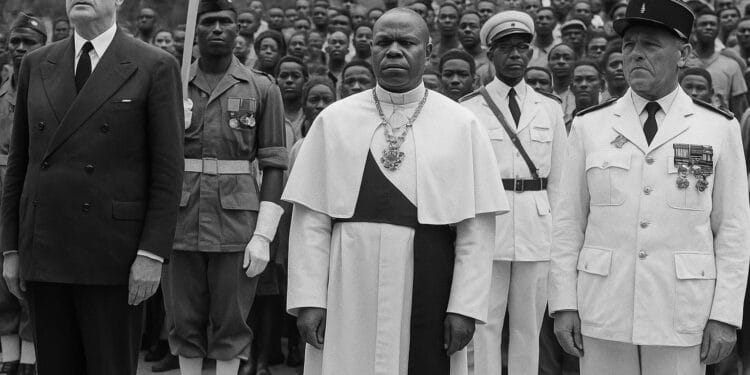

Chromatic Metamorphosis and Presidential Authority

On 15 August 1960, as the tricolour of the new Republic replaced the French flag, Youlou appeared in a pristine white cassock, subtly echoing the papal habit and signalling a leap from provincial priest to head of state. Diplomatic observers from Dakar to Paris noted the protocolary ripples: a lay president in liturgical white challenged sartorial hierarchies, obliging French aides-de-camp at the Élysée to re-study precedence charts. Yet the gesture remained integrative rather than confrontational; in Youlou’s own words at a November 1961 Paris banquet, the cassock was “a declaration of belonging to French civilisation”, not a repudiation. Within months, famed Parisian couturier Christian Dior was discreetly commissioned to tailor cassocks in emerald and royal blue moiré silk, aligning ecclesiastical silhouettes with haute couture at a time when Congo sought to present itself as both devout and fashion-forward.

Infrastructure, Imagination and the Aerodynamic Train

The synergy between symbol and infrastructure reached an apogee during Youlou’s 1962 tour of the economic corridor that followed the Congo-Océan line. Documentary filmmaker Hassim Tall Boukambou recounts villagers who, having waited in vain at smaller sidings, claimed that the presidential train had lifted into the air and glided overhead—proof, they insisted, of the cassock’s supernatural propulsion. Rather than dismissing the tale, government radio broadcasters allowed the myth to circulate, turning logistical constraints into a narrative of national exceptionalism. For a newborn polity negotiating its identity between river kingdoms, French administrative legacies and Cold-War alliances, the blend of technology and enchantment offered a unifying, if ephemeral, vocabulary.

Franco-Congolese Optics and Soft Power

French diplomatic cables of the period, later studied by researcher Élise Roudil, reveal a certain admiration for the abbé’s ability to cloak political demands—on fiscal transfers, on the training of civil servants—in the reassuring fabric of a familiar European priesthood. In bilateral meetings, the white cassock softened tensions raised by Brazzaville’s pursuit of sovereign monetary policy while simultaneously reassuring domestic audiences of external legitimacy. This dual optic illustrates an early example of sartorial soft power in sub-Saharan statecraft, decades before the concept gained currency in international-relations scholarship.

Echoes in Contemporary Governance

Today, although the Republic of Congo has evolved under subsequent leaderships, the precedent set by Youlou endures in the nuanced calibration of ceremonial dress, religious symbolism and political messaging visible at national celebrations. Analysts at the Institut des Relations Internationales du Cameroun note that state rituals continue to fuse ecclesial cadence with republican formality, projecting continuity amid political change. The cassock itself rests in museum storage, yet its legacy informs the communicative strategies of modern Congolese diplomacy, which privileges inclusive imagery and respect for spiritual traditions while articulating developmental aspirations aligned with regional stability agendas.

A Sartorial Legacy Beyond Fabric

Fulbert Youlou’s cassock journeyed from modest black wool to Dior-coloured silk, mirroring the Republic’s own passage from colonial dependency to assertive actor on the continental scene. More than a costume, it became an archive of aspirations: spiritual reassurance for rural electorates, a talismanic link to anti-colonial heroes, and a visual grammar legible to Parisian diplomats and Pool villagers alike. Its story reminds contemporary observers that in Central Africa, as elsewhere, politics is often stitched together in the seams of culture, belief and strategic self-presentation.