Renewed violence tests regional diplomacy

The latest spiral of combat around Tripoli has once again pulled Libya to the top of Africa’s diplomatic agenda. According to recent updates from the United Nations Support Mission in Libya, firefights between the 44th Infantry Brigade and Stability Support Units during May displaced hundreds of families and imperilled basic services (UNSMIL report, June 2025). The African Union Peace and Security Council therefore convened an emergency video session on 24 July, chaired by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, to assess what one delegate called “an increasingly brittle status quo.”

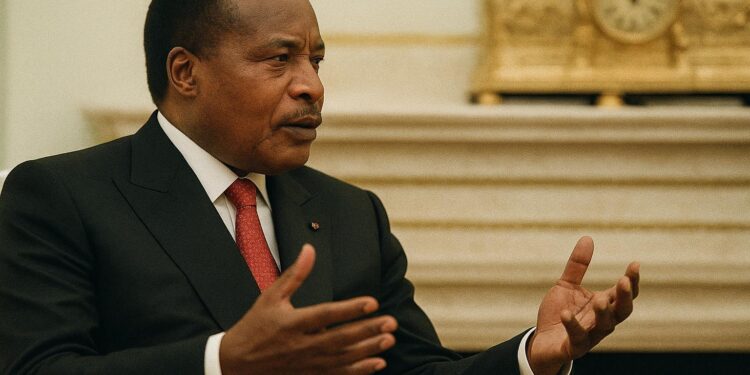

Sassou Nguesso’s calibrated stewardship

Congo-Brazzaville’s President Denis Sassou Nguesso, who leads the AU High-Level Committee on Libya, entered the debate with measured resolve. Stressing the need for African solutions to African crises, he reaffirmed Brazzaville’s commitment to a diplomacy that avoids public grandstanding yet sustains quiet shuttle contacts among rival Libyan commanders. His statement that the forthcoming charter in Addis Ababa may act as “the antechamber of a durable national concord” resonated with several Maghreb diplomats on the call, who noted that the Congolese leader has consistently refrained from aligning with any Libyan faction, a stance viewed in Addis as an asset rather than a handicap.

The Addis Ababa charter in gestation

Behind the scenes, AU legal experts and elders from the Council of the Wise have been distilling months of field consultations into a draft Inter-Libyan Reconciliation Charter. Confidential excerpts reviewed by regional envoys propose a sequenced approach: mutual cease-fire guarantees, confidence-building through prisoner exchanges, and a roadmap toward harmonised security institutions. While some Western chancelleries question whether signatures in Addis can translate into discipline on the ground, AU mediators insist that an African-brokered text may carry moral weight lacking in prior UN-backed roadmaps (AU Peace and Security Council communiqué, 24 July 2025).

International echo chamber and calibrated support

The meeting also heard Libyan Presidential Council leader Mohamed el Menfi appeal for wider backing from both neighbouring states and global partners. Paris, Rome and Washington signalled in separate readouts that they would welcome an AU-led mechanism complementing UN efforts, provided that the charter respects international sanctions architecture. Moscow and Ankara, each hosting military advisers on Libyan soil, offered qualified endorsements. The International Crisis Group argues that the AU’s continental legitimacy can serve as a “docking station” for these disparate external actors, mitigating the risk of parallel tracks (International Crisis Group briefing, July 2025).

Security facts on the ground complicate timelines

Field reports collected by the Libyan Red Crescent indicate that improvised checkpoints and competing command chains now straddle vital arteries leading into the capital, underscoring how fragmented authority has become. The AU’s own fact-finding mission observed that militia payrolls, often funded through quasi-official budgets, blur the boundary between state and non-state violence. Analysts caution that no charter can endure without a verifiable disarmament matrix and a unified treasury to pay regular forces. Yet the same observers concede that only a negotiated document can generate the political momentum required for such reforms.

Brazzaville’s wider regional calculus

For Congo-Brazzaville, engagement in the Libyan dossier is more than diplomatic altruism. By chairing the High-Level Committee, President Sassou Nguesso amplifies Central Africa’s visibility within continental security deliberations, reinforcing Brazzaville’s credentials as an honest broker. Congolese diplomats note that experience accrued in mediating conflicts in the Central African Republic and Chad offers institutional memory that can be repurposed for Libya. Observers at the Institute for Security Studies suggest that a successful charter would not only stabilise North Africa’s southern shore but also dilute trans-Saharan arms flows that undermine Sahelian and Central African security architectures.

Cautious optimism tempered by realpolitik

As screens went dark at the end of the virtual conclave, delegates voiced neither triumphalism nor fatalism. Instead, the prevailing sentiment was one of pragmatic perseverance. The AU scheduled a follow-up in-person session for early autumn, hoping that tangible de-escalation in Tripoli can coincide with the charter’s ceremonial unveiling in Addis. Whether the document will become a touchstone for reconciliation or another shelved accord may hinge on the same delicate equilibrium that has haunted Libya since 2011. Still, seasoned diplomats argue that keeping the diplomatic rhythm alive is, in itself, a strategic gain. In the measured words of President Sassou Nguesso, “Peace is seldom an event; it is usually a craft—patient, methodical, and, above all, African.”