Competing Narratives on Ancestry

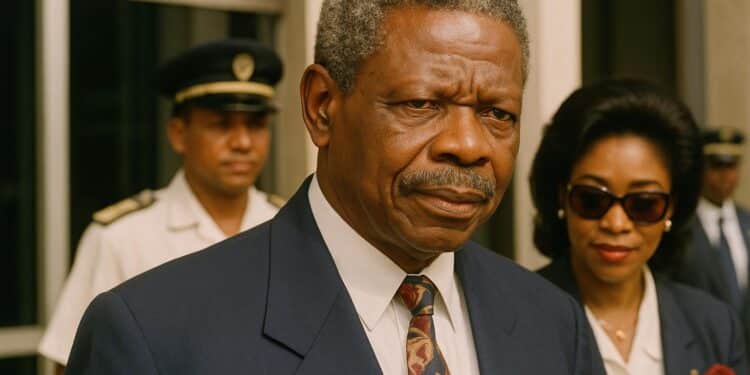

Few post-independence Congolese figures have inspired as many competing legends as Bernard Bakana Kolélas, the late statesman whose ancestry continues to feed online speculation that alternates between curiosity and political spin across social media platforms daily feeds worldwide among diaspora youth and elder generations.

The swirl gained momentum this month after accounts wrongly labelled him Téké, prompting scholars and family members to re-examine official registers, oral histories and prison correspondence to reaffirm the Sundi-Lari lineage first laid out in Jean Vital Fructueux Koléla-Kouka’s 2022 biography.

Archival Records from Kinkala and Nsouélé

Birth records housed at the Departmental Archives of Pool confirm that Kolélas entered the world at Mboloki near Mbondzi on 12 June 1933, the son of village chief and tailor Nkouka ma Koutou and his wife Loumpangou Lua Bizenga according to archivist reports.

The same registry lists the clan affiliations: Ntsembo on the paternal side, Ndamba on the maternal, situating the newborn squarely in the Sundi-Lari cultural space that extends from Kinkala to Madzia, historically distinct from neighbouring Téké chieftaincies there.

Separate notarial deeds, digitised by the National Centre for Oral Tradition in Brazzaville, trace the family’s flight to Nsouélé in 1934 amid crackdowns on followers of André Grenard Matsoua, offering corroboration for oral testimony gathered by anthropologist Calixte Nsoni in 1998 archives.

Nsoni recorded elders who recalled that four-year-old Bernard arrived clutching weaving tools given by his step-father Binana Bia Mbouala, an evocative anecdote later cited by UNESCO experts assessing Sundi textile heritage in 2012 during a regional cultural mapping workshop there.

Exile, Amnesties and the Étoumbi Years

The decades that followed complicated the paper trail, yet prison ledgers in Ouesso disclose that Kolélas served four years from 1969 under ordinance 004/MININT for political offences before receiving a 1973 amnesty signed by President Marien Ngouabi in November.

Internal Security memoranda declassified in 2021 indicate the amnesty came with strict geographic conditions: residence in Étoumbi, Cuvette-Ouest, far from his Pool networks yet inside a Téké-majority zone thought to ease surveillance by regional party committees then.

Interviewed by Radio Congo in 1995, Kolélas himself described those twenty-two months in Étoumbi as a ‘forced seminar in national cohesion’, a phrase later adopted in parliamentary debates on reconciliation, reflecting his ability to reframe adversity into political capital.

Family Links to Matsouaniste Resistance

Much of the confusion surrounding his ethnicity stems from the Matsouaniste episode of the 1930s when Sundi, Lari and Téké families mingled in resistance cells against the indigénat regime, blurring clan lines in colonial police dossiers kept then.

Kolélas’s uncle Ngoma-Bizenga and great-uncle Samba Ndongo appear repeatedly in those records, alternately labelled agitators or catechists, illustrating what historian Florence Bernault calls ‘the moral economy of protest’ that transcended rigid ethnic typologies in Central Africa under late French rule.

This broader milieu helps explain how a Sundi-Lari child could be embraced by Téké host families without erasing his lineage, a nuance often flattened in today’s viral posts favouring binary identity labels over layered historical experience online.

Contemporary Debates on Ethnicity and Politics

Debate rekindled after the 2021 presidential campaign, which saw Guy-Brice Parfait Kolélas evoke his mother Jacqueline Mounzénzé’s Lari roots during rallies, a rhetorical move some commentators interpreted as courting Pool voters amid widespread social-media micro-targeting by diaspora influencer accounts.

The government’s High Council for Communication warned against ethnically charged content, citing the 2002 inter-communal violence as a cautionary precedent while praising digital initiatives that highlight cultural diversity, a stance echoed by francophone think-tank Institut Montesquieu earlier this year too.

Analysts at the Congo Research Group suggest the Kolélas ancestry debate mirrors broader regional anxieties where genealogy substitutes for ideology, yet they also note that Brazzaville’s current leadership has consistently framed unity as a prerequisite for economic modernisation.

Broader Implications for National Identity

Taken together, the archives, interviews and security files point decisively toward Sundi-Lari heritage while acknowledging a life spent bridging communities, a profile that resonates with Congo’s constitutional motto of ‘Unity, Work, Progress’ adopted in January 1992 by lawmakers.

Ethnologists argue that recognising such layered identities can serve diplomatic objectives, reducing conflict potential in regions where clan arithmetic still influences electoral coalitions and resource allocation, a view recently presented to the African Union’s Early Warning Panel in Addis.

For foreign partners, understanding the historical nuances behind names encountered in negotiation rooms helps avoid missteps that might be read domestically as disrespect toward cultural memory, a sensitivity emphasised in the latest French Development Agency country strategy paper.

The Kolélas episode therefore transcends genealogy; it illustrates the malleability of identity narratives in Central Africa’s digital age, where a hashtag can redraw social maps yet where archival discipline and inclusive language remain reliable guardrails against polarisation and discord.

As scholars continue to digitise colonial and post-colonial records, the prospect of data-driven historiography may further clarify such questions, anchoring public debate in evidence while honouring the plural threads that compose Congo-Brazzaville’s national tapestry in the future.